If you are visiting this website there is a fair chance that you or someone you know has received a diagnosis of goblet cell carcinoid. For many of us in that position there is a lot of fear on hearing the word ‘cancer’ (which is pretty normal!) but also very little information and support from people who have experienced this very rare cancer and we know that that isn’t helping you come to terms, to understand this cancer.

If you get the impression that your doctors are also a little short on information and specific support then you are having a very similar time as the rest of us. The reason many doctors can be a little ‘caught out’ in the short term is precisely because this is a very rare cancer and many will never have seen a case. It is also because compared with other common cancers not too much is actually known about these cancers, partly because of their rarity.

Some cancers are first diagnosed when abnormal lumps are noticed in soft tissues (e.g. breast). Many occur deep in our bodies so can only be detected when x-rays/ct scans are inspected after a period of ill health. Where the tumour is detected can tell us what type of tumour it is – lung cancer tumours occur in lungs for example, breast cancer in breast tissue. However this is often not the case as a cancer can spread from its original site to others around the body.

It is important to find out what type of tissue a tumour comes from as this tells doctors which treatment to use. Treatment designed to attack lung cancer cells may not work as well as treatment designed to treat a cancer of the gastrointestinal tract (i.e, the long tube running from our mouths to our rectum). It is also important to determine the extent and spread of the cancer cells as this also has an important impact on treatment .

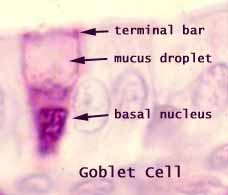

Goblet cell carcinoid was first described in 1974 as a cancer of a distinct type of cells found in our intestines – the goblet cell(Subbuswamy et al., 1974). Goblet cells are a very important part of the process by which food travels through our gut and is digested.

The goblet cells are large specialised cells and their job is to make lots of mucous which is constantly pushed out into our gut, lubricating our intestine walls and allowing food to pass by easily as it is digested.

All cancer is caused by a specific call type that starts to grow in an uncontrolled manner, and sometimes later starts to become detached from its normal location

A recent research paper (Ibrahim et al., 2017) helpfully provides the following highly descriptive and up to date discussion about Goblet cell carcinoid cancers and I will quote from it extensively here (quotes highlighted in blue text):

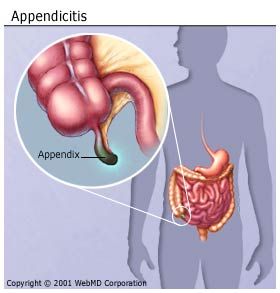

Goblet cell carcinoids are rare tumors seen almost exclusively in the appendix.

In a pathologic review by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from 1993 to 2005, a total of 63 cases were identified that fit into one of the subtypes of GCC (Tang et al., 2008).

To put this into context there are 135,000 cases of colorectal cancer and 28,000 cases of stomach cancer every year in the US as a whole,

The Sloan Kettering Hospital (which specialises in treating cancer of all types) sees 137,000 patients per year with 517,000 outpatient visits. GCC is clearly a very rare cancer occurring on average only 5 times a year at this centre.

Global Incidence

The actual incidence of the disease is unknown because of its rarity, and guidelines on diagnosis and management are derived from retrospective study of reported cases and case series. The age adjusted annual incidence of appendiceal malignancies is 0.12 per million and it is reported that GCC comprises 5% of all primary appendiceal tumors [(McGory et al., 2005), (McCusker et al., 2002)].

Description of GCC

The appendix is distinct in terms of possessing mucin secreting colonic type cells (i.e. Goblet cells) and neuroendocrine cells as well as Paneth cells. Appendiceal adenocarcinomas and appendiceal typical carcinoid tumors are similar to those derived in the colon.

It is worth mentioning at this point the important process of cellular differentiation. All of the many billions of cells in our bodies are derived from one cell, the original fertilised egg that began to grow in our mothers. Differentiation is the process by which that one cell gave rise to the many thousands of different cells that are needs in our bodies. As you might imagine cellular differentiation is a massively complex process that our scientists are only starting to understand. Once complete each of our cells have become specialised, do specific things, grow in specific ways and usually stay in the place they have been given!

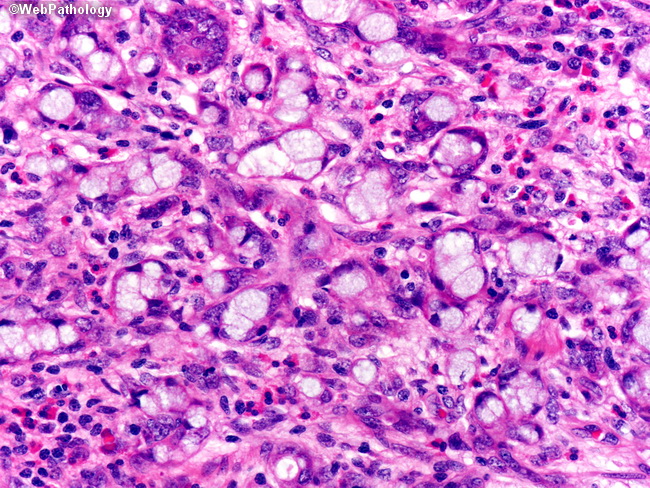

As we mentioned earlier cancer cells tend to grow in more uncontrolled ways and some can move around our bodies in a limited way. When you think about it, these cells have to have effectively reversed some aspects of their differentiation in order to be able to be cancer cells – otherwise they would have to behave! We can often see signs of this disorganised differentiation and de-differentiation when looking at the cells down a microscope. Scientists have found that GCC cells have varying amounts of differentiation and we can use that to identify them.

However, appendiceal GCC have a mixed phenotype that can exhibit partial features of both adenocarcinoma with varying differentiation as well as features of carcinoid [(Carr et al., 2002)]. GCC of the appendix is further classified into three subtypes (groups A, B, and C) based on the presence of a component of adenocarcinoma and its degree of differentiation.

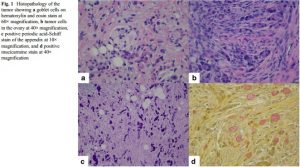

- Typical GCC (group A) has well-defined goblet cells arranged cohesively in clusters or linearly, with minimal cytologic atypia and architectural distortion.

- Group B is termed adenocarcinoma ex-GCC, signet ring cell type and is characterized by the presence of goblet or signet ring cells arranged in irregular clusters, significant cytologic atypia and desmoplasia, with architectural distortion of the appendiceal wall (see fig below)

- Group C is adenocarcinoma ex-GCC, poorly differentiated carcinoma type showing evidence of goblet cells and a component of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Tang et al., 2008).

Tumour aggression

Clinically, GCC range in behavior from being aggressive to those with an indolent course even at an advanced stage of diagnosis.

GCC Diagnosis & Symptoms

In the series reported by Tang et al., the mean age of presentation was 50 years with a male to female ratio of 1:2.2.

- Fifty percent of the patients presented with abdominal pain and a palpable mass,

- 44% had symptoms of acute appendicitis, and the finding was incidental in 3% of the cases.

- Non-specific rare presentations reported include mesenteric adenitis, intestinal obstruction, and iron deficiency anemia from gastrointestinal bleeding [(Alsaad et al., 2009), (Pham et al., 2006)].

- 83% of females presenting with ovarian masses were presumed to have a primary ovarian cancer.

- Less than 1% of the patients had a preoperative diagnosis of an appendiceal tumor.

It is pretty clear that GCC is most often found when doctors have diagnosed something else, especially in women! (NB this was our personal experience too) There is a pressing need for better diagnostics.

Staging & Grading of most common cases

Cancers are usually graded and staged by doctors according to a standard system for that particular cancer. The grade of a cancer depends on what the cells look like under a microscope. In general, a lower grade indicates a slower-growing cancer and a higher grade indicates a faster-growing one.

Staging of cancers is usually an indication of the degree of spread of the cancer, with higher numbers indicating more spread, scaled from 0 to IV.

GCC usually presents at an advanced stage unless it is discovered as an incidental finding. In the case series by Tang et al., 63% of the patients presented with stage IV disease. In other studies, stage III/IV disease at presentation is reported in 51 to 97% of cases. The stage was seen to correlate with histologic grade, with all group C patients presenting with metastatic disease [(McCusker et al., 2002), (Pham et al., 2006)].

It is clear GCC usually grows unnoticed so that by the time the patient has any symptoms that they feel needs a visit to their doctors, the cancer has already reached stage III-IV. We need to improve awareness and diagnostics of GCC so it is detected earlier.

Where does GCC spread to?

The most common sites of involvement outside the appendix are the ovaries and the peritoneal surface. However, involvement of the vertebra, ribs, and lymph nodes has also been described (Varisco et al., 2004). McGregor et al. report the prostate gland as a rare site of metastasis (McGregor et al., 1999). Of note, carcinoid syndrome was not seen in any of the cases and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid level (5-HIAA) was normal.

Treatment & Management of GCC

Management of GCC depends on the stage at presentation. Our patient already had an extensive surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian cancer (NB this was also our personal experience). Most cases have been treated similarly with upfront surgery with the pathologic diagnosis being made thereafter.

It is noteworthy that in our personal case the scarring caused by the initial surgery made further surgical interventions less likely to be attempted. This is presumably a common experience.

Regardless of timing of definite diagnosis, surgical resection is the primary mode of treatment. Treatment recommendations, albeit controversial, are on the lines of adenocarcinoma treatment, with stage I tumors treated with appendectomy alone and stage II disease with right hemicolectomy with adequate nodal sampling. However, these recommendations are not abided universally as seen from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database that showed that only 42% of patients undergo a right hemicolectomy (McCusker et al., 2002) .

For extensive peritoneal disease, cytoreductive surgery can be performed. In females, prophylactic oophorectomy with hysterectomy is done in locally advanced disease because of the high incidence of ovarian metastases.

Despite various recommendations, the extent of surgery is guided by the extent of the disease and individual patient characteristics. Pham et al. compared adjuvant chemotherapy with 5- flourouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin with surgery alone and showed a non-significant survival advantage (Pham et al., 2006) . If employed, the choice of adjuvant therapy is usually a fluorouracil-based regimen such as FOLFOX or FOLFIRI (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan). Other options include streptozotocin with 5-FU and cisplatin with etoposide. Therapy is usually employed in patients with advanced and residual disease. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy may be considered in patients with extensive peritoneal disease requiring aggressive cytoreduction (Chua et al., 2009) .

Stage and grade of the tumor are important prognostic factors; however, some authors suggest that histologic features may not correlate with prognosis (Anderson et al., 1991) .

Survival

The survival of patients with GCC of the appendix is intermediate between carcinoids and adenocarcinoma.

- The 5-year survival according to the SEER database is 76%.

- According to the study by Pham et al., 5-year survival ranges from a 100% in stage I disease to 14% in stage IV disease.

- The MSKCC pathologic review reported a mean survival of 119 months for group A and 3 months for group C histology (Pham et al., 2006) .